***reading instruction: all information (history, recipes, and recipes comparisons) about ragù alla bolognese is on the left side, and mapo tofu is on the right side.

RAGù ALLA BOLOGNESE

The evolution of Ragù alla Bolognese

The 1st offical deposited recipe for Ragù alla Bolognese

filed at the Chamber of Commerce of Bologna on October 17, 1982, by the Bologna Delegation of the Italian Academy of Cuisine.

The most recent offical deposited recipe for Ragù alla Bolognese

updated recipe, Chamber of Commerce of Bologna on April 21, 2023, by the Bologna Delegation of the Italian Academy of Cuisine.

There are millions of copies and variations of recipes for this dish, as it is a staple in Italian families. There is no way to identify a single “best” version. The reason I selected these two recipes is that they are considered the official versions recognized by the Italian Academy of Cuisine—one being the original and the other a later revision. Although they differ in small ways, the core structure remains the same, which aligns well with my research theme of “origin and development.”

Below, I will compare these two recipes, highlight the key takeaways, and include some of my own insights from making ragù based on them—focusing on what we can learn in order to create a version of Ragù alla Bolognese that suits your own taste.

Deep Dive into Ragù alla Bolognese Recipes

key takeaways:

The 1982 recipe was designed for everyday Italian home cooking, with fewer specifics about ingredient, preparation and cooking times. The updated 2023 version includes more detailed steps, reducing confusion and making it more accessible for a global audience. It is clearer, easier to follow, and more consistent to execute.

The major flavor updates involve the tomato-to-meat ratio and the allowance of red wine in the 2023 recipe. These changes create a richer, more meat-forward ragù. As a regional specialty, the updated recipe aligns more closely with the culinary identity of Emilia-Romagna and feels more “on brand” for Ragù alla Bolognese.

Slow cook is essential when making the best ragù. Although both recipes suggest a 2–3 hour simmer, cooking time ultimately depends on your stove and your preferred meat tenderness. I personally recommend a low, slow simmer for 4–5 hours to achieve deeper flavor and softer texture.

Having prepared both recipes, I prefer the 2023 version on a rainy or cold day, when I want something rich and comforting. The 1982 version suits casual cooking days with friends, when I am more relaxed and paying less attention to technique.

There are two additional elements I want to highlight based on my personal taste:

Soffritto proportions (onion, celery, carrot)

This could be an entire discussion on its own. Most sources suggest a 1:1:2 ratio, but it’s important to adjust these proportions to match your preferences. I prefer a sweeter ragù, so I use a 1:1:3 ratio. Think of 1:1:2 as a baseline formula, then adjust and experiment as you develop your own version.Use of milk and butter

These are traditionally suggested when serving the ragù with dry pasta. I think of milk and butter as “cheat” ingredients: not just that apply only on dry pasta if your other produce isn’t exceptionally fresh, try use these additions to help maintaining the richness and balance ragù.

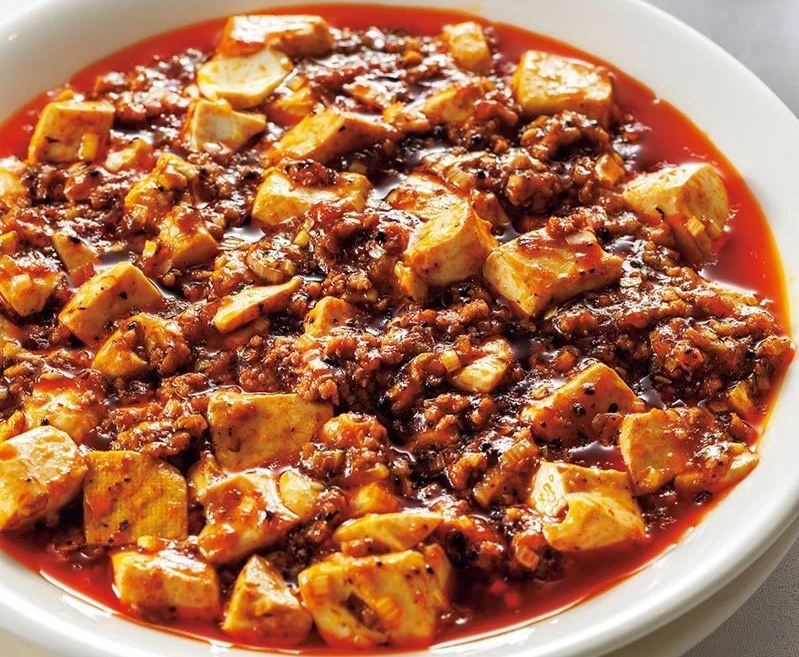

麻婆豆腐 (Mapo Tofu)

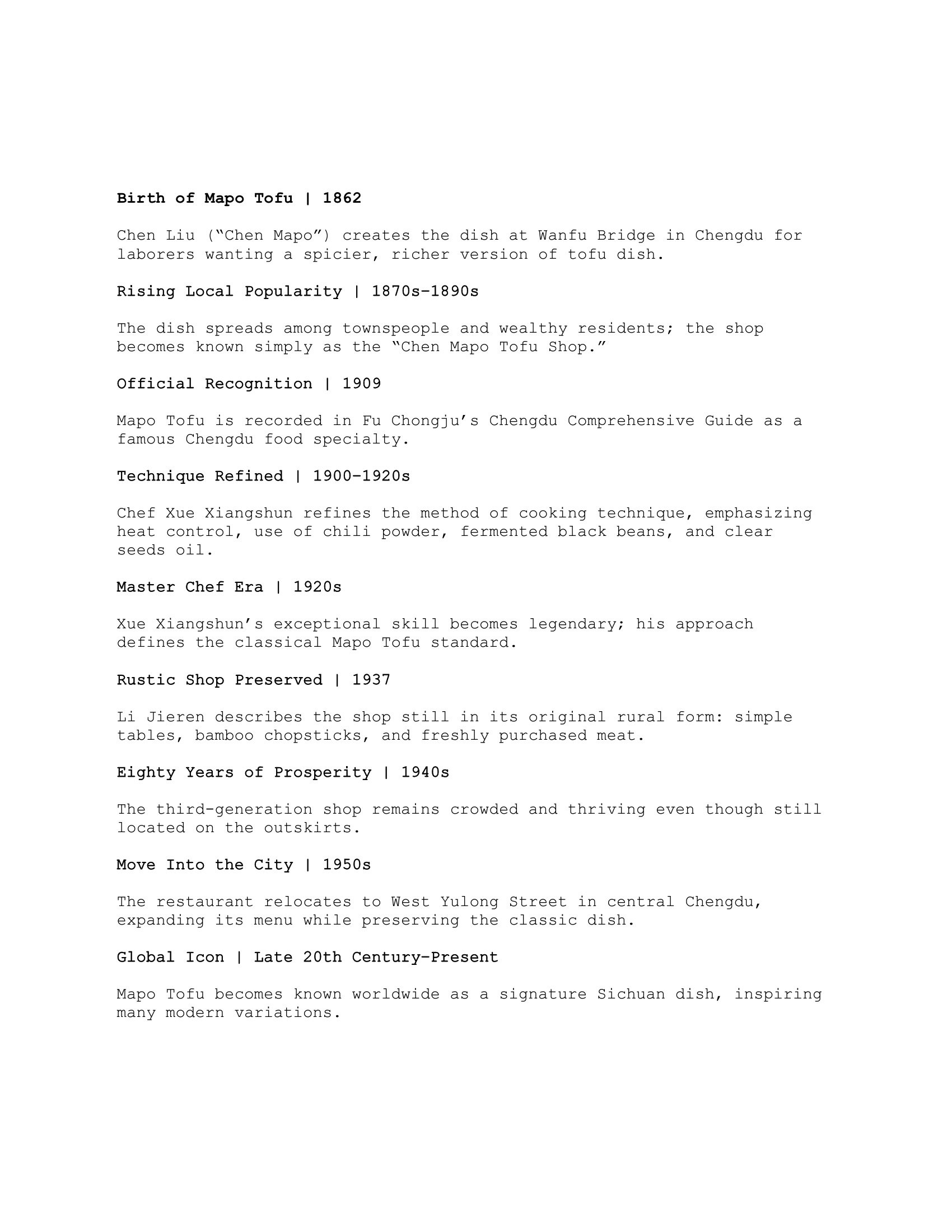

The evolution of 麻婆豆腐 (Mapo Tofu)

The Traditional Chen Mapo Tofu recipe

published in The Famous Recipes of China 中国名菜谱 (1958)

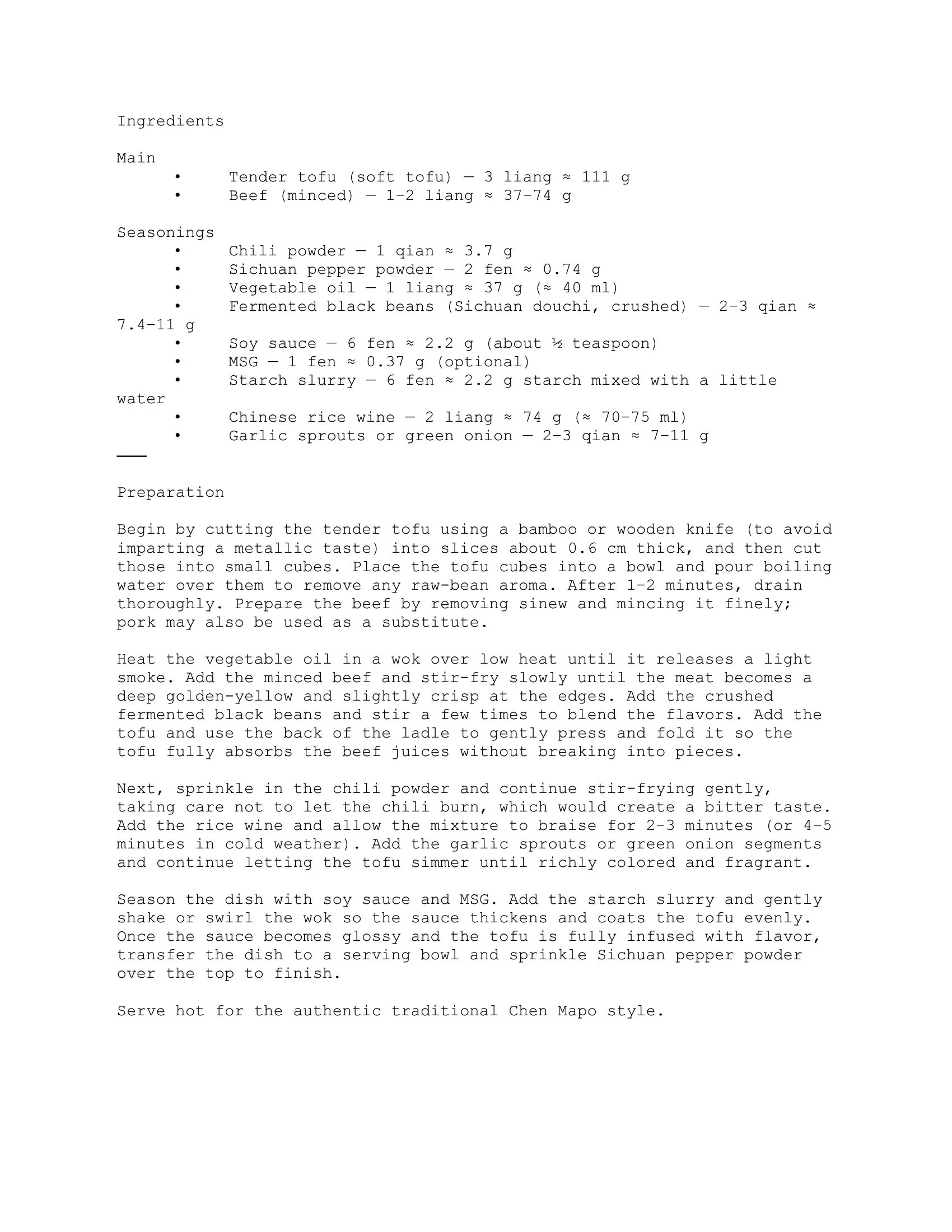

The summary of recipe for Mapo Tofu made by Kenchi Chen

reference from Japan China Cuisine Association (Public Interest Incorporated Association) 公益社団法人日本中国料理協会

Finding which Mapo Tofu recipes to use has been one of the most challenging parts of this project. Because many Asian culinary traditions developed before modern copyright systems, it is difficult to trace an exact “original” recipe. I attempted to locate a version closest to the one created by Chen Mapo herself, and the most authoritative source I found is the recipe recorded in The Famous Recipes of China 《中国名菜谱》. I chose this recipe because it represents a nationally recognized culinary reference, preserves regional authenticity, and continues to influence modern Chinese cooking.

The second recipe I selected is not Chinese but Japanese. Chen Kenichi, a pioneering figure in bringing Sichuan cuisine to a global audience, adapted Mapo Tofu for Japanese kitchens. His interpretation marked a breakthrough moment: by presenting Sichuan-style Mapo Tofu on mainstream Japanese television, he helped transform the dish into a culinary sensation both in Japan and internationally. His version aligns well with the theme of this project—origin and evolution—by showing how a regional specialty can be reinterpreted and popularized across cultures.

Deep Dive into Mapo Tofu Recipes

key takeaways:

The main differences between the two recipes come down to ingredients and preparation style. The traditional recipe focuses on a very straightforward set of components: beef, douchi 豆豉, chili powder, and Sichuan pepper 四川花椒 (which has a short preservation window and is difficult to find fresh outside Sichuan). Every element is used with purpose and restraint, giving the dish a cleaner, sharper, and more direct mala flavor.

Kenichi’s version, on the other hand, brings in more layers—doubanjiang, Tianmianjiang 甜面酱 (a key ingredient in modern Sichuan cooking), soy sauce, pork instead of beef, and a thicker starch slurry. These additions build a richer, rounder flavor that feels more approachable and especially well suited for serving with rice, which is how most people outside Sichuan enjoy Mapo Tofu.

Heat and texture treatment also differ noticeably. The traditional method parboils thin slices of tofu to tighten their structure before adding them to the wok, keeping the final dish lighter and more aromatic. Kenichi’s version uses larger tofu cubes and simmers them briefly to achieve a firmer, “dancing” texture before folding them into the sauce. This results in a thicker, smoother dish with a sauce that clings much more tightly to the tofu.

The traditional recipe captures Mapo Tofu at its origin—rustic, bold, and straightforward—and it requires more technical skill to achieve good results. In contrast, Kenichi Chen’s version highlights the dish’s evolution, shaped by cross-cultural influence. All the ingredients he uses are easier to find in Asian supermarkets around the world, making his approach more accessible for home cooks outside China.

Having made both, I personally tend to choose Kenichi Chen’s version. As someone living outside China and not professionally trained, his recipe—while not exactly easy—is much more achievable with the ingredients available to me.

There are two additional notes based on my personal experience:

Protein choice

The traditional recipe uses beef for a firmer, more aromatic foundation, while the pork in Kenichi’s version adds natural sweetness and roundness. I would say this choice depends largely on where you live and what is affordable or common in your region. If pork is more accessible where you are, there is no reason not to choose it, and vice versa.

Balancing mala

The traditional recipe finishes with Sichuan pepper powder to create a clean, floral numbing effect. Kenichi incorporates the peppercorns into the simmering broth, which softens the intensity. As a Sichuanese, I will always choose the Sichuan pepper-forward finish without hesitation. If you can get your hands on good-quality Sichuan pepper—even the dried packaged kind—you can toast it lightly in a saucepan and crush it into powder. It produces a similar aroma to fresh peppercorns; my mom taught me this method, so I can vouch for how authentic it tastes.

How I Connect Ragù alla Bolognese with Mapo Tofu

Ragù alla Bolognese not only redefined how the world views “Italian meat sauce,” but also exemplifies Italy’s slow-cooking traditions and culinary aesthetics. Evolving from adapted French techniques and shaped by regional Italian influences, it ultimately became codified in the official recipe filed in Bologna, representing Italian cuisine to the world.

Mapo Tofu, though emerging from an entirely different culinary evolution, follows a similar trajectory. It developed from a simple, flavorful roadside dish for laborers into a defining symbol of Sichuan cuisine, celebrated for its numbing mala heat and deep umami. Unlike slow-cooked ragù, Mapo Tofu requires precision, high heat, and craftsmanship in a short cooking time, yet it extracts the same essence of culinary art through technique. Adapted over time to local needs and refined by chefs and culinary pioneers, it grew alongside the forces of modernization and globalization.

Both dishes represent the essence of the culinary art and culture of their respective countries. They are simple, basic, and timeless—dishes you would find on the table of many families and on the menus of countless Italian and Chinese restaurants. Although their histories span only a few hundred years, their flavors have continued to evolve through globalization as spices, ingredients, and tastes change. At the same time, they remain deeply rooted in tradition and are dishes that can be passed down through generations.